Mail can be moved in many different ways, as the newest series of Europa stamps shows… but did you know that this process was once done with the help of wagons that whizzed by in a metal tunnel, deep underneath the bustling streets of London?

We’re talking about the UK's Post Office Underground Railway, charmingly later referred to as Mail Rail, a driverless electric underground railway system used to move post between sorting offices in London. It was constructed throughout the 1910s and 1920s with combined efforts of the Post Office and the Underground Electric Railways Company of London, inspired by the Chicago Tunnel Company’s underground railway freight tunnel network.

The railway began its operations on December 3rd, 1927. It ran from east to west and stretched six and a half miles between the East End and Paddington. Consisting of eight stations, the largest existed below Mount Pleasant. At its peak, a new train of mail arrived at the station every six minutes. Employees had to work very quickly in order to remove all the mail whose destination was Mount Pleasant and load any mail destined for other offices. There was a great camaraderie between staff members, who generally spent their entire careers working on the system. You can see evidence of this from the relics left behind on walls near major mailbag chutes: a dartboard, finished paintings, and a collection of stamps.

Only three other cities attempted an underground postal railway: Munich, Germany in 1910, Lucerne, Switzerland in 1927, and Zurich, Switzerland in 1937. All closed their operations in the 80’s. The Chicago Tunnel Company sometimes delivered parcels, but its main function was not associated with the Post Office.

By 2003, only three stations of London’s Post Office Underground Railway remained. Royal Mail had reported that using Mail Rail cost five times more than using road transport for the same task, and so, after 75 years of operation, the railway shut down on May 31st, 2003. Today, the British Postal Museum and Archive (BPMA) has been undertaking efforts to conserve parts of the Mail Rail.

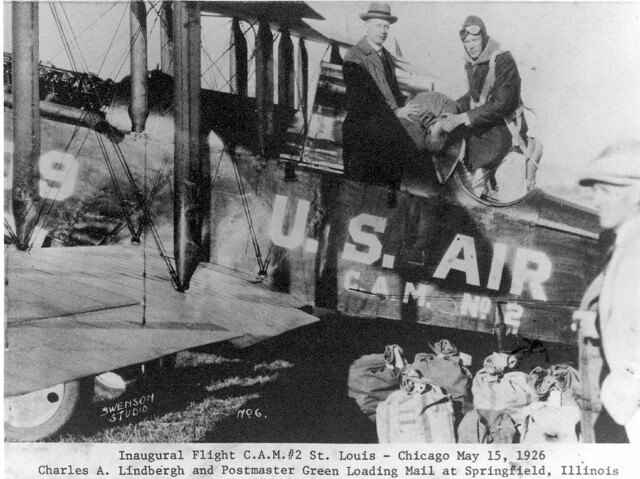

Rail Mail wagons, by Yuriy Akopov on Flickr.

You can learn more about their endeavors and about the railway itself at the BPMA Museum’s Mail Rail page and fantastic Flickr gallery. If you’re in the area, they currently have a free photography exhibition about the Mail Rail that you can visit!